DAY 2:

THE SEAFOOD INDUSTRY

PROJECT MISSION

The Lesson Mission is what you (the student) will be able to do after the lesson is over.

DIRECTIONS: Today, you will not write your Lesson Mission. You will do a week long project to demonstrate that you have completed the mission.

The Lesson Mission for today is: I can describe the geography and economy of the Gulf Coastal Region during and just after the Reconstruction Era and explain how different things effected the economy and culture of the region.

DIRECTIONS: Today, you will not write your Lesson Mission. You will do a week long project to demonstrate that you have completed the mission.

The Lesson Mission for today is: I can describe the geography and economy of the Gulf Coastal Region during and just after the Reconstruction Era and explain how different things effected the economy and culture of the region.

TODAY'S ASSIGNMENT

DIRECTIONS: Read today's reading about the Seafood Industries of the Gulf Coast Region. Then work on your magazine page. To stay on schedule, you need to read the article and create today's page by the end of the day.

In the early 19th century, small boatyards existed along the entire Gulf Coast. They manufactured and repaired barges and flat-bottomed schooners suitable to the waters of the region.

In the mid- to late 19th century, the catboat was built and used extensively along the Gulf Coast. Catboats were small, wooden fishing boats with a flat bottom, double sails, and could accommodate two fishermen. During the off-season, catboat races often occurred. A famous catboat was the Royal Flush, built by Captain Willie Johnson in 1889. Because Captain Johnson constructed her so well, the Royal Flush did not lose a race in thirty-four years.

The Schooner

As interest in the seafood industry grew in the late 19th century, fishermen required boats larger than the catboat to haul in the large catches. Schooners, a fast-sailing craft with at least two masts and sails, replaced catboats. The coast schooners were inspired by those used in Baltimore for fishing enterprises carrying goods along sea trade routes, and the tradition of building them was deep in coastal naval enterprises.

In 1893, a hurricane destroyed most of the schooner fleet on the Gulf Coast. This led local boat builders to design a specific style of schooner that was best suited to the waters along the Gulf Coast. These waterways included bayous, oyster reefs, and shallow bays and lakes. The schooner was a boat characterized by a broad beam, shallow draft, and increased sail power. The schooner was fifty to sixty feet long, although some were larger. Because of its shallow draft, the Schooner could easily sail in and out of waters with little depth, and its size allowed larger crews to work on the decks.

The sail power of the Schooner enabled the ship to drag the oyster dredges and shrimp seines when they became full with the bivalves and crustaceans. These working crafts were both durable and graceful when “under sail.” Apprentice carpenters learning the boatbuilding trade in 1893 could expect to earn 75 cents a day for fifteen hours of work as they worked to replace the lost schooner fleet.

The Lugger

By 1915, most fishermen had switched to gasoline-powered boats, the lugger, which could drag the heavy otter trawl, a funnel-shaped net thirty to thirty-five feet long, to efficiently capture more shrimp. The lugger was sturdy, seaworthy, versatile, and had only a three-foot draw. It became the fishing boat of choice. Shipbuilding was an exclusively male craft with skills learned from generation to generation. Often fathers taught their sons the trade.

The Fishing Industry

Several different types of seafood industries developed because of the different sea life in the Gulf of Mexico. The Mississippi River along with several other marshes and wetlands empty into the Gulf. This allowed fisherman to easy fish for saltwater and freshwater fish and shellfish. The major seafood industries that developed were saltwater fin fish, freshwater fin fish, crawfish, crabs, shrimp, and oysters.

The Saltwater Fin Fish Industry

Gag Grouper

Gag Grouper

The Gulf Region has a rich heritage of fishing for saltwater fin fish. Species including grouper, black drum, red snapper, cobia, flounder, greater amberjack, and gray triggerfish are especially popular for their fresh mild flavor, and are used in numerous seafood dishes. These tasty species are often broiled, baked, or grilled, but are also used in dishes.

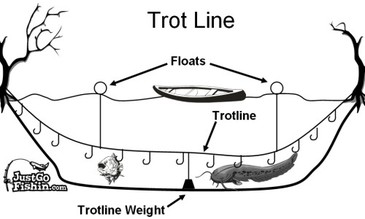

The saltwater fin fish industry in the Gulf has changed greatly since the earliest days of settlement. Native Americans harvested fish in the shallow coastal marshes, bays and lakes by using trot lines, wooden traps, hoop nets, and also by spearing and using bows and arrows. The earliest European settlers sometimes used seine nets that were launched by hand or wind-powered boats, but were hauled ashore by hand, which was a hard process because of the heavy weight of the nets.

Red Fish or Red Drum

Red Fish or Red Drum

In the twentieth century, motorized boats and more durable nets make the harvest process of saltwater fin fish more faster and easier. Modern processing facilities have also made it easier than ever for consumers to enjoy this seafood bounty. Today, seafood markets and grocery stores commonly offer drum, snapper, grouper filets, amberjack, and triggerfish.

The Fresh Water Fin Fish Industry

Bowfin

Bowfin

The Gulf has a long history and heritage of harvesting and consuming freshwater fin fish. Catfish are the most common and popular among the commercially caught wild freshwater fish. Other species include freshwater drum, bowfin, and sometimes buffalo fish. These fish are cooked in a variety of ways that are delicious. They are often deep fried as filets or even in ground balls, sautéed, baked, broiled and even grilled. In many areas of the Gulf, they are also used as a main ingredient in courtbouillon, a fish stew that has its roots in the coastal areas of Cajun Louisiana. Gaspergoux is also also a popular ingredient in New Orleans, Louisiana and Mobile, Alabama for making an étoufée which is usually served over a bed of rice. Chouxpique roe is also harvested for use as caviar.

|

Early Native Americans caught fish in lakes, bayous and rivers in the Gulf Region using a variety of methods. In the early 1700s, the Acolapissa tribe used corn-meal dough or meat as a bait on hooks and the lines were tied to their dug-out pirogues, from which they caught fish weighing on average fifteen to twenty pounds.

Most of the early Native American techniques for catching freshwater fish were adopted by Acadians, Europeans and Africans in Louisiana. Methods include the trot-line mentioned above, rabbit-vine hoop nets, cone-shaped traps made of wooden slats and sometimes spear or bow-fishing. Some of these techniques are still used by contemporary commercial freshwater fishers in the Gulf. Yet, during the twentieth century, the advent of motorized boats and synthetic nets has generally made fishing more efficient.

|

Catfish

Catfish

The town of Des Allemands in Louisiana is billed as the “catfish capital of the universe,” and every June the Louisiana Catfish Festival attracts thousands of people who come to eat this tender fresh water fish with the mild flavor. At the festival, catfish is served fried in a po-boy sandwich or on a platter, in a Cajun-style sauce piquante, and also in boulettes, which are patties or balls made of ground catfish, potatoes, onions and spices, and then served either in a soup or gravy, or as a sandwich.

The Crab Industry

|

Native Americans and early settlers harvested crabs in the brackish waters of coastal marshes, lakes, bays and bayous. In the earliest days of settlement in the Gulf, people harvested only enough crabs for their families to eat. They caught crabs by using bait on a line that was pulled up.

Commercial crab harvest techniques have improved gradually over the twentieth century. In the early 1900s, crabbers often used trot-lines and nets to harvest them in the coastal marshes and lakes. Sometimes crabbers hung wax myrtle bushes and bait on trot-lines. Fishers would pull up the line, and knock the crabs into dip nets. At that time, most crabbers harvested as part of a seasonal occupation along with logging, Spanish moss picking, and alligator hunting.

|

The modern blue crab industry began in the 1880s when commercial fisheries became more developed. In the early days, most of the crabs were sold locally to hotels and restaurants in the Gulf area, because the lack of refrigeration prevented shipping longer distances.

Finally in 1924, the first crab processing plant in Morgan City, Louisiana developed a process that picked meat from crabs so that it could be shipped all over the United States. By 1927, hard crab catches exceeded 1 million pounds, while soft-shell crab catches were 137,000 pounds. Because of packing plants and refrigeration, Louisiana blue crabs can now be enjoyed across the U.S. and internationally as well. When one goes to enjoy crabs in the Chesapeake region, which is known for their famous boiled crabs, they are actually eating imported Gulf Coast crabs.

Shrimp

Gulf shrimp are enjoyed by food lovers around the world in a variety of dishes including grilled, sautéed, fried, dried, and boiled shrimp, as well as in seafood gumbo, shrimp remoulade, jambalaya, stuffed peppers and in many kinds of soups, casseroles, and pasta dishes.

White Shrimp

White Shrimp

Several varieties of shrimp are harvested in Louisiana’s coastal waters. Large white shrimp are preferred for making boiled and barbecued shrimp, and they have a limited in-shore season in the late summer. Large brown shrimp are generally caught in deeper salt waters year-round, and have a firmer texture than white shrimp. While brown and white shrimp make up the majority of the Gulf shrimp harvest, pink shrimp are caught in the mid-Winter months, when other varieties are in low supply. Other less-known varieties include sea bob, Roughneck, Royal Red, Rock, and River shrimp.

Commercial shrimping began in the Gulf in the 1870s. In those early years, shrimpers used either seine nets from the shore, or used small skiffs with nets to harvest the shrimp and then pull up the heavy nets from the shore. Shrimpers often harvested on a part-time basis before the growth of the modern shrimping industry in the 1930s.

Royal Red Shrimp

Royal Red Shrimp

After World War I, shrimpers began to use automobile motors in boats to cover greater distances and to pull the heavy trawling nets to harvest shrimp. By the 1930s, shrimpers from the Atlantic Coast and Florida introduced the larger motorized trawlers, which enabled shrimpers in the rest of the Gulf to go farther from shore where bountiful shrimp stocks exist. The use of large booms and winches on these trawlers enabled shrimpers to catch up to forty or fifty barrels of shrimp on a trip. In the 1930s, Morgan City, Louisiana emerged as the new center of shrimp processing. Shrimp canneries grew as a big business in the early twentieth century. But before the 1930s, most non-canned shrimp was consumed locally because it was difficult to keep shrimp fresh for transporting longer distances. As refrigeration technology improved and ice plants began to be established on the coast after World War II, fishermen were able to keep shrimp fresher for a longer period of time.

The motorized trawlers allowed faster transport to markets and the delivery of fresh shrimp that had been placed on ice. This enabled people outside of the Gulf coastal regions to enjoy shrimp and helped to grow the industry. Today, fresh Gulf shrimp are enjoyed around the world thanks to the development of modern transportation and technology. Shrimping remains an important part of the Gulf coastal heritage for many families and communities.

Oysters

Oysters are enjoyed raw or grilled the half-shell, and also cooked in popular dishes such as Oysters Rockefeller, Oysters Bienville, and fried for a platter or a po-boy sandwich.

Historically, oysters have grown naturally in the Gulf Coast region on reefs in brackish water, where salt and fresh water blends to form the perfect environment for oysters. Oysters can only thrive if they can grow elevated above the muddy flats of the bay and estuary bottoms, so the natural reefs provide the ideal environment. Early settlers and Native Americans in Louisiana harvested these reef oysters.

Immigrants from France and Croatia helped to develop the modern oyster industry in the Gulf during the 1800s. Many of these immigrants were familiar with oyster cultivation, and helped to expand the oyster farming business in the Gulf.

Before the 1880s, almost all oysters in Louisiana were consumed locally. With the advent of canning and refrigeration, Gulf oysters began to be exported beyond the Gulf. Before the 1880s, most oyster consumers outside of the Gulf Coast generally ate smaller and lesser grade oysters (known as steamers or steam cannery oysters). The largest and best ones, known as raw-shop or counter oysters, were consumed locally in oyster bars. At the turn of the century, oysters generally sold for $3-$4 a barrel, and barrels contained 3 bushels, the equivalent of 2 sacks today. A sack of oysters today sells for around $35.

The Gulf Region began to regulate oyster farming in the 1880s by overseeing the leasing of public waters to oyster fishermen. Many other oysters are farmed in privately owned waters.

oyster reef

oyster reef

Oysters are farmed by building a reef with cultch materials, most often shell of rock to provide a bed that is raised above the soft muddy bottom, and then planting oyster seed shells, known as spat, which take around three years to grow to maturity on the reef. Oysters grow in brackish water estuaries along the coast, but are moved temporarily to salt water to give the oysters a salty flavor.

The oyster harvest is a job that requires hard physical labor. In the past, oystermen traveled in small skiffs and harvested the oysters with tongs, long-handled rakes, to gather the oysters from the reef. In the mid twentieth century, the industry began to use motorized boats and mechanical dredges to harvest the oysters. Although the mechanical dredges enable oystermen to harvest a larger amount of oysters more efficiently, the process is still hard work and requires great stamina and strength. So as you enjoy the oysters while dining, remember the process of getting the oyster to market requires a lot of hard work from oystermen.

The Canning Industry

Seafood Factory

Seafood Factory

The first seafood factory on the Gulf Coast was Lopez, Elmer and Company, opened in 1881, in Mississippi. Other factories soon developed, and by 1892, the canning of oysters and shrimp was the chief industry of the coast. Men, women, and children worked in the seafood factories, in the shrimp-packing sheds, and in the oyster-shucking business.

|

The need for labor increased as the industry grew, and workers from Baltimore, most of them of European descent and known as Bohemians, were imported into the area. Soon other European fishermen and seafood workers arrived from Greece, Italy, France, and Yugoslavia.

Many of the seafood plants closed during the summer months for boat repair. Despite some labor problems, the seafood industry continued to grow. In 1903, for instance, Lopez and Dukate and Company in Biloxi was thought to be the largest plant of its kind in the world, with the company handling up to 4,000 barrels of oysters a day, requiring the services of sixty boats and hundreds of workers.

|

Processing Shrimp

|

When canning factories opened, there were plenty of railroads. Gulf seafood could be shipped all over the U.S. without spoiling. Canning was a thriving business. Shrimp was one of the seafoods that were canned and shipped.

Shrimp processing for example, begins when factories take the shrimp directly from the boats as they dock beside the company piers. As the shrimp are unloaded, they are dumped into what is called a "conch-catcher", where a water pump pushes the shrimp into a wet tank, and other things, such as small fish or crabs, are prevented from going into it. Next, the shrimp are dropped onto a conveyor belt. They move rapidly to the point where they drop into boxes for a weight check.

|

From that point, they are emptied into a food pump which moves them up into the peeling machines. Everything is accompanied by great amounts of water used to move the produce, separate debris and clean the shrimp. The shrimp then move by conveyor belt and drop onto the rubber rollers that do most of the peeling. The peeled shrimp then go into a washer shaped like a half-moon, with an inside of rubber and shells that move back and forth to separate the remaining loose hulls from the shrimp.

|

From the washer, they move to another food pump that pumps them up to separators-- two rollers, one moving clockwise and one counter- clockwise, which separate the remaining hulls. The hulls drop onto troughs below, while the peeled shrimp move into metal chutes, called graders. These graders size the shrimp by using a set of bars that can be raised or lowered. The larger shrimp are stopped by the first bar and are directed from the grading plates into containers below.

Once the shrimp are "sized", they are then dumped onto packing tables, where about twenty people, wearing long rubber or plastic gloves, check the shrimp for any remaining foreign materials, weigh them in five-pound lots, and place them into bags in which they also put ice water. Then they are placed in boxes and marked as to size.

|

From that point, the boxes of shrimp are placed on racks holding 1100 pounds of shrimp. The shrimp are packed with dry ice or artificial ice until freezing methods developed in the early 1900s. These shrimp are kept cold and shipped to local and nearby grocers, markets, and restaurants.

|

In factories where shrimp are canned for large-scale distribution, much the same process may be followed, until the final grading and inspection, when workers hand-pack the shrimp into empty cans, which they get from an overhead track. The final factory process is the cooking of the shrimp. The cans are placed in steel baskets in pressure-cookers, where they remain for twelve minutes at 250° Fahrenheit.

The processing of shrimp was only one of several important types of seafood processing on the Gulf Coast. A large number of people in the Gulf Coast had jobs in fin fish and oyster processing factories. There are over 1,500 licensed commercial shrimp boats on the coast today, supplying more than eighty seafood processing plants and dealers.

|

Other Seafood Processing

So, the development of the seafood industry does a wonderful job of illustrating several important ways the environment impacts the people of a region. As you seen, the Fishing industry demonstrates how people in a region rely on their natural resources to develop their economy. It also shows how one industry effects the development and success of other industries. The Fishing industry makes boatbuilding necessary. It also makes it necessary to develop processing factories and shipping companies. It helps stock restaurants, markets, and grocery stores. Finally, the environment effects the culture of a region. It determines the food people eat and what they do for fun. It determines the jobs people get and customs that develop.