FOR THE CHILDREN

Child labor was a major issue at the turn of the Twentieth Century. Families struggling to survive relied on their children's wages to help support the family. Industries preferred to hire children because they could be paid less and were easier to manage. Many managers beat and neglected the children. Children were often injured working with dangerous machinery. They often became sick because they worked in poorly ventilated, unsanitary conditions. Many children worked bare foot in the middle of the winter. The factories were not heated in the winter or cooled in the summer. Many industries also deprived children of the sunlight they needed to stay healthy. Many Progressives of the time felt that child labor needed to be heavily reformed and even banned. They soon came together and worked hard to do something about it.

|

Child labor reform began in the 1870s with labor unions who worked to change child labor laws. The first efforts to create a national child labor reform organization began in Alabama in 1902. A preacher named Edgar G. Murphy created the Alabama Child Labor Committee. It was the first child labor reform organization in the United States.

In 1902, Florence Kelley, the head of the National Consumers League and Lillian Wald, the founder of Henry Street Settlement began the New York Child Labor Committee to investigate the working conditions and treatment of child workers in the city of New York. |

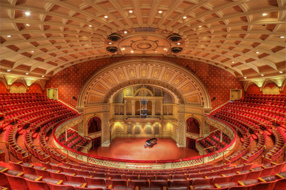

Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall

In 1903 the Alabama Child Labor Committee and the New York Child Labor Committee met and started planning a National Child Labor Committee. They held a conference in Carnegie Hall in New York City on April 15, 1904 and invited anyone interested in child labor reform. On April 25, 1904, they officially started the National Child Labor Committee. The leaders of the organization included some of the most well known social progressives including Jane Addams and Lillian Wald. The NCLC became the largest and most important social welfare project of the Progressive Era.

The Capitol Building is where Congress meets.

The Capitol Building is where Congress meets.

Their approach was much different than the labor union's approach. The NCLC went in and investigated industries in all major cities in each state. Some did formal investigations. Others went undercover pretending to be workers and they documented what they saw. At the same time, another team of workers studied the law and worked to write better laws that regulated child labor to present to Congress. In 1907, the NCLC gained not only the support of Congress but was also chartered by Congress. This means Congress paid the NCLC to work on child labor reform for the government.

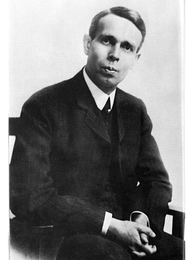

Lewis HIne

Lewis HIne

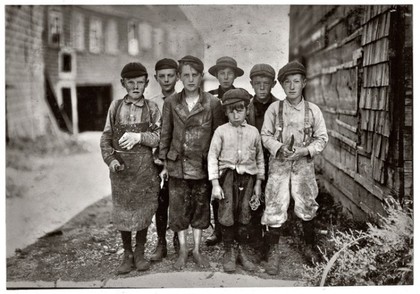

The first step the NCLC took under their new charter was to hire photographer Lewis Hine. Hine was an anthropologist and famous photographer who left his teaching career to be an investigator for the NCLC. He went into industries and photographed children and other industrial workers. To get into theses industries, he pretended to be a Bible salesman, a postcard salesman, and an industrial photographer making a record of factory machinery in order. There were industries who were suspicious of Hine and would not allow him to come in at all. When this happened, he would unload his camera equipment outside of the canneries, mines, factories, farms, and sweatshops and he would photograph the children when they came to work and when they left work.

His photographs were published in newspapers and magazines all over the world and they told a powerful story. Theses pictures informed the world of the abuse and neglect children faced in the workplace. Not only, did his photographs help to increase membership in the NCLC but it created national concern. Now, the whole nation was ready for child labor reform.

His photographs were published in newspapers and magazines all over the world and they told a powerful story. Theses pictures informed the world of the abuse and neglect children faced in the workplace. Not only, did his photographs help to increase membership in the NCLC but it created national concern. Now, the whole nation was ready for child labor reform.

Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

In 1916 President Woodrow Wilson signed into the law the Keating-Owen Act that heavily regulated child labor to the point it was almost banned altogether. It was a major victory for the NCLC. One month before it was supposed to be implemented into law, Southern Textile industrialists challenged the law. They went to the Supreme Court and the Supreme Court ruled that laws banning child labor were unconstitutional.

What started as a major victory ended in defeat. So, the NCLC made a new goal. They began working on a constitutional amendment banning child labor, but in the meantime, they appealed to state law makers. State law makers all over the nation began to relate child labor on the state level. In 1918, Mississippi was the final state to make education mandatory. Children in every state now had to go to school from ages 6 to 16.