Title

Howard Zinn first learned of the Ludlow Massacre from a song by Woody Guthrie, which Zinn says, “nobody had ever mentioned in any of my history courses.” To help future generations of students learn about Ludlow in their history courses, we offer here an interview with Zinn about the significance of Ludlow and his description of the history from A People’s History of the United States.

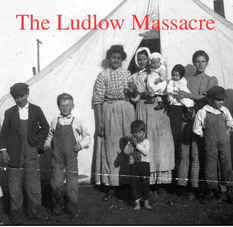

Striking family at Ludlow shortly before the April 20, 1914 massacre.

Shortly after Woodrow Wilson took office there began in Colorado one of the most bitter and violent struggles between workers and corporate capital in the history of the country.

This was the Colorado coal strike that began in September 1913 and culminated in the “Ludlow Massacre” of April 1914. Eleven thousand miners in southern Colorado … worked for the Colorado Fuel & Iron Corporation, which was owned by the Rockefeller family. Aroused by the murder of one of their organizers, they went on strike against low pay, dangerous conditions, and feudal domination of their lives in towns completely controlled by the mining companies. …

When the strike began, the miners were immediately evicted from their shacks in the mining towns. Aided by the United Mine Workers Union, they set up tents in the nearby hills and carried on the strike, the picketing, from these tent colonies.

The Ludlow Tent Colony, before the massacre.

One of 1,200 striking miner families in the Ludlow Tent Colony.

The gunmen hired by the Rockefeller interests—the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency—using Gatling guns and rifles, raided the tent colonies. The death list of miners grew, but they hung on, drove back an armored train in a gun battle, fought to keep out strikebreakers. With the miners resisting, refusing to give in, the mines not able to operate, the Colorado governor (referred to by a Rockefeller mine manager as ‘our little cowboy governor’) called out the National Guard, with the Rockefellers supplying the Guard’s wages.

The miners at first thought the Guard was sent to protect them, and greeted its arrival with flags and cheers. They soon found out the Guard was there to destroy the strike. The Guard brought strikebreakers in under cover of night, not telling them there was a strike. Guardsmen beat miners, arrested them by the hundreds, rode down with their horses parades of women in the streets of Trinidad, the central town in the area. And still the miners refused to give in. When they lasted through the cold winter of 1913-1914, it became clear that extraordinary measures would be needed to break the strike.

In April 1914, two National Guard companies were stationed in the hills overlooking the largest tent colony of strikers, the one at Ludlow, housing a thousand men, women, children. On the morning of April 20, a machine gun attack began on the tents. The miners fired back. Their leader, …, was lured up into the hills to discuss a truce, then shot to death by a company of National Guardsmen. The women and children dug pits beneath the tents to escape the gunfire. At dusk, the Guard moved down from the hills with torches, set fire to the tents, and the families fled into the hills; thirteen people were killed by gunfire.

The following day, a telephone linesman going through the ruins of the Ludlow tent colony lifted an iron cot covering a pit in one of the tents and found the charred, twisted bodies of eleven children and two women. This became known as the Ludlow Massacre.

The Ludlow Tent Colony ruins.

The news spread quickly over the country. In Denver, the United Mine Workers issued a “Call to Arms”—“Gather together for defensive purposes all arms and ammunition legally available.” Three hundred armed strikers marched from other tent colonies into the Ludlow area, cut telephone and telegraph wires, and prepared for battle. Railroad workers refused to take soldiers from Trinidad to Ludlow. At Colorado Springs, three hundred union miners walked off their jobs and headed for the Trinidad district, carrying revolvers, rifles, shotguns.

Armed strikers.

In Trinidad itself, miners attended a funeral service for the twenty-six dead at Ludlow, then walked from the funeral to a nearby building, where arms were stacked for them. They picked up rifles and moved into the hills, destroying mines, killing mine guards, exploding mine shafts. The press reported that “the hills in every direction seem suddenly to be alive with men.”

In Denver, eighty-two soldiers in a company on a troop train headed for Trinidad refused to go. The press reported: “The men declared they would not engage in the shooting of women and children. They hissed the 350 men who did start and shouted imprecations at them.”

Five thousand people demonstrated in the rain on the lawn in front of the state capital at Denver asking that the National Guard officers at Ludlow be tried for murder, denouncing the governor as an accessory. The Denver Cigar Makers Union voted to send five hundred armed men to Ludlow and Trinidad. Women in the United Garment Workers Union in Denver announced four hundred of their members had volunteered as nurses to help the strikers.

All over the country there were meetings, demonstrations. Pickets marched in front of the Rockefeller office at 26 Broadway, New York City. A minister protested in front of the church where Rockefeller sometimes gave sermons, and was clubbed by the police.

The New York Times carried an editorial on the events in Colorado, which were not attracting international attention. The Times emphasis was not on the atrocity that had occurred, but on the mistake in tactics that had been made. Its editorial on the Ludlow Massacre began: “Somebody blundered …” Two days later, with the miners armed and in the hills of the mine district, the Times wrote: “With the deadliest weapons of civilization in the hands of savage-mined men, there can be no telling to what lengths the war in Colorado will go unless it is quelled by force … The President should turn his attention from Mexico long enough to take stern measures in Colorado.”

Clip from the The Survey newspaper. Image: WikiCommons.

The governor of Colorado ask for federal troops to restore order, and Woodrow Wilson complied. This accomplished, the strike petered out. Congressional committees came in and took thousands of pages of testimony. The union had not won recognition. Sixty-six men, women, and children had been killed. Not one militiaman or mine guard had been indicted for crime.

[…]

The Times had referred to Mexico. On the morning that the bodies were discovered in the tent pit at Ludlow, American warships were attacking Vera Cruz, a city on the coast of Mexico—bombarding it, occupying it, leaving a hundred Mexicans dead—because Mexico had arrested American sailors and refused to apologize to the United States with a twenty-one gun salute. Could patriotic fervor and the military spirit cover up class struggle? Unemployment, hard times, were growing in 1914. Could guns divert attention and create some national consensus against an external enemy? It surely was a coincidence—the bombardment of Vera Cruz, the attack on the Ludlow colony. Or perhaps it was, as someone once described human history, “the natural selection of accidents.” Perhaps the affair in Mexico was an instinctual response of the system for its own survival, to create a unity of fighting purpose among a people torn by internal conflict.

The bombardment of Vera Cruz was a small incident. But in four months the First World War would begin in Europe.

--By Howard Zinn from A People’s History of the United States, pages 346-349.

Song: Ludlow MassacreWords and Music by Woody Guthrie

It was early springtime when the strike was on,

They drove us miners out of doors,

Out from the houses that the Company owned,

We moved into tents up at old Ludlow.

I was worried bad about my children,

Soldiers guarding the railroad bridge,

Every once in a while a bullet would fly,

Kick up gravel under my feet.

We were so afraid you would kill our children,

We dug us a cave that was seven foot deep,

Carried our young ones and pregnant women

Down inside the cave to sleep.

That very night your soldiers waited,

Until all us miners were asleep,

You snuck around our little tent town,

Soaked our tents with your kerosene.

Striking family at Ludlow shortly before the April 20, 1914 massacre.

Shortly after Woodrow Wilson took office there began in Colorado one of the most bitter and violent struggles between workers and corporate capital in the history of the country.

This was the Colorado coal strike that began in September 1913 and culminated in the “Ludlow Massacre” of April 1914. Eleven thousand miners in southern Colorado … worked for the Colorado Fuel & Iron Corporation, which was owned by the Rockefeller family. Aroused by the murder of one of their organizers, they went on strike against low pay, dangerous conditions, and feudal domination of their lives in towns completely controlled by the mining companies. …

When the strike began, the miners were immediately evicted from their shacks in the mining towns. Aided by the United Mine Workers Union, they set up tents in the nearby hills and carried on the strike, the picketing, from these tent colonies.

The Ludlow Tent Colony, before the massacre.

One of 1,200 striking miner families in the Ludlow Tent Colony.

The gunmen hired by the Rockefeller interests—the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency—using Gatling guns and rifles, raided the tent colonies. The death list of miners grew, but they hung on, drove back an armored train in a gun battle, fought to keep out strikebreakers. With the miners resisting, refusing to give in, the mines not able to operate, the Colorado governor (referred to by a Rockefeller mine manager as ‘our little cowboy governor’) called out the National Guard, with the Rockefellers supplying the Guard’s wages.

The miners at first thought the Guard was sent to protect them, and greeted its arrival with flags and cheers. They soon found out the Guard was there to destroy the strike. The Guard brought strikebreakers in under cover of night, not telling them there was a strike. Guardsmen beat miners, arrested them by the hundreds, rode down with their horses parades of women in the streets of Trinidad, the central town in the area. And still the miners refused to give in. When they lasted through the cold winter of 1913-1914, it became clear that extraordinary measures would be needed to break the strike.

In April 1914, two National Guard companies were stationed in the hills overlooking the largest tent colony of strikers, the one at Ludlow, housing a thousand men, women, children. On the morning of April 20, a machine gun attack began on the tents. The miners fired back. Their leader, …, was lured up into the hills to discuss a truce, then shot to death by a company of National Guardsmen. The women and children dug pits beneath the tents to escape the gunfire. At dusk, the Guard moved down from the hills with torches, set fire to the tents, and the families fled into the hills; thirteen people were killed by gunfire.

The following day, a telephone linesman going through the ruins of the Ludlow tent colony lifted an iron cot covering a pit in one of the tents and found the charred, twisted bodies of eleven children and two women. This became known as the Ludlow Massacre.

The Ludlow Tent Colony ruins.

The news spread quickly over the country. In Denver, the United Mine Workers issued a “Call to Arms”—“Gather together for defensive purposes all arms and ammunition legally available.” Three hundred armed strikers marched from other tent colonies into the Ludlow area, cut telephone and telegraph wires, and prepared for battle. Railroad workers refused to take soldiers from Trinidad to Ludlow. At Colorado Springs, three hundred union miners walked off their jobs and headed for the Trinidad district, carrying revolvers, rifles, shotguns.

Armed strikers.

In Trinidad itself, miners attended a funeral service for the twenty-six dead at Ludlow, then walked from the funeral to a nearby building, where arms were stacked for them. They picked up rifles and moved into the hills, destroying mines, killing mine guards, exploding mine shafts. The press reported that “the hills in every direction seem suddenly to be alive with men.”

In Denver, eighty-two soldiers in a company on a troop train headed for Trinidad refused to go. The press reported: “The men declared they would not engage in the shooting of women and children. They hissed the 350 men who did start and shouted imprecations at them.”

Five thousand people demonstrated in the rain on the lawn in front of the state capital at Denver asking that the National Guard officers at Ludlow be tried for murder, denouncing the governor as an accessory. The Denver Cigar Makers Union voted to send five hundred armed men to Ludlow and Trinidad. Women in the United Garment Workers Union in Denver announced four hundred of their members had volunteered as nurses to help the strikers.

All over the country there were meetings, demonstrations. Pickets marched in front of the Rockefeller office at 26 Broadway, New York City. A minister protested in front of the church where Rockefeller sometimes gave sermons, and was clubbed by the police.

The New York Times carried an editorial on the events in Colorado, which were not attracting international attention. The Times emphasis was not on the atrocity that had occurred, but on the mistake in tactics that had been made. Its editorial on the Ludlow Massacre began: “Somebody blundered …” Two days later, with the miners armed and in the hills of the mine district, the Times wrote: “With the deadliest weapons of civilization in the hands of savage-mined men, there can be no telling to what lengths the war in Colorado will go unless it is quelled by force … The President should turn his attention from Mexico long enough to take stern measures in Colorado.”

Clip from the The Survey newspaper. Image: WikiCommons.

The governor of Colorado ask for federal troops to restore order, and Woodrow Wilson complied. This accomplished, the strike petered out. Congressional committees came in and took thousands of pages of testimony. The union had not won recognition. Sixty-six men, women, and children had been killed. Not one militiaman or mine guard had been indicted for crime.

[…]

The Times had referred to Mexico. On the morning that the bodies were discovered in the tent pit at Ludlow, American warships were attacking Vera Cruz, a city on the coast of Mexico—bombarding it, occupying it, leaving a hundred Mexicans dead—because Mexico had arrested American sailors and refused to apologize to the United States with a twenty-one gun salute. Could patriotic fervor and the military spirit cover up class struggle? Unemployment, hard times, were growing in 1914. Could guns divert attention and create some national consensus against an external enemy? It surely was a coincidence—the bombardment of Vera Cruz, the attack on the Ludlow colony. Or perhaps it was, as someone once described human history, “the natural selection of accidents.” Perhaps the affair in Mexico was an instinctual response of the system for its own survival, to create a unity of fighting purpose among a people torn by internal conflict.

The bombardment of Vera Cruz was a small incident. But in four months the First World War would begin in Europe.

--By Howard Zinn from A People’s History of the United States, pages 346-349.

Song: Ludlow MassacreWords and Music by Woody Guthrie

It was early springtime when the strike was on,

They drove us miners out of doors,

Out from the houses that the Company owned,

We moved into tents up at old Ludlow.

I was worried bad about my children,

Soldiers guarding the railroad bridge,

Every once in a while a bullet would fly,

Kick up gravel under my feet.

We were so afraid you would kill our children,

We dug us a cave that was seven foot deep,

Carried our young ones and pregnant women

Down inside the cave to sleep.

That very night your soldiers waited,

Until all us miners were asleep,

You snuck around our little tent town,

Soaked our tents with your kerosene.

Click on the icon below to visit the Ludlow Massacre Interactive Website.