A Violent Battle

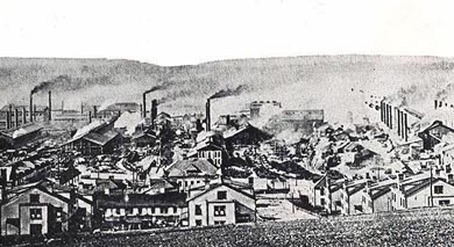

Homestead Steel Mill

Homestead Steel Mill

The Homestead Steel Mill Strike in 1892 was a strike at Carnegie Steel at the Homestead Steel Mill in Homestead Pennsylvania. It was organized by the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers Union and it was different that the major strikes that occurred before it. Earlier strikes were unorganized. There were no real leaders or plans of action. They were worker revolts. The Homestead Steel Strike was different. It was organized by the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers Union also called the AA. It had a purpose and a goal. It was organized and well planned.

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie

It all began when Andrew Carnegie, owner of Carnegie Steel, made Henry Clay Frick manager of the Homestead Steel Mill in 1881 . The steel industry was booming and profits were up. So the AA asked for a pay increase for their hard work. Henry Frick told them no. In fact he told them they were going to receive a 22% pay decrease. Frick did this because he knew people would drop out of the union because workers would not be able to afford their union dues. He was hoping this would get rid of the AA and prevent them from having influence over the way the company was run.

Henry Frick

Henry Frick

The AA tried to work with Frick on a collective bargaining agreement, but on the evening of June 28, 1892, Frick locked all union workers out of the Homestead Steel Mill. When members of the Knights of Labor who worked at the mill found out, they walked off the job and joined the AA in the strike. When workers at Carnegie plants in Pittsburgh, Duquesne, Union Mills, and Beaver Falls heard the news they all walked out and joined the strike as well.

Alan Pinkerton of the Pinkerton Detective Agency

Alan Pinkerton of the Pinkerton Detective Agency

Frick placed ads for replacement workers in newspapers as far away as Boston, St. Louis, and even Europe. He planned to open the mill again with nonunion workers on July 6. In April 1892, Frick hired the Pinkerton National Detective Agency to provide security at the plant. The plan was to have three hundred Pinkerton agents secretly assemble and come down the river quietly on barges at night, on July 5, armed with Winchester rifles. They would force the strikers to disband and break up the picket lines allowing the new workers to come in.

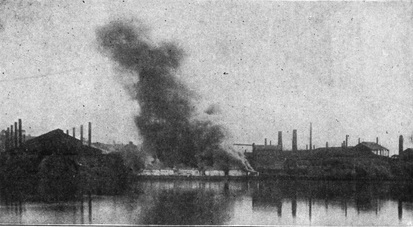

The Pinkerton barges were set on fire.

The Pinkerton barges were set on fire.

The strikers had heard about Frick's plan and were prepared for the agents. The strikers blew the plant whistle at 2:30 a.m and a large crowd of families began to keep pace with the Pinkertons' boats. Some of them fired at the Pinkerton's boats but at this point, no one was injured. The families tore down the barbed wire fence and took the Homestead Mill. Some families threw stones at the Pinkertons' boats but were ordered by strike leaders to stop. When the Pinkertons got off of the barge, shots were fired. No one truly knows who fired first. The boat captain hired by the Pinkertons said that the workmen fired first and the Pinkertons did not shoot back until three of their men had been shot. The New York Times reported that the Pinkerton's shot first and wounded a worker named William Foy.

Strikers using scrap metal as a shield in the metal yard at Homestead Mill.

Strikers using scrap metal as a shield in the metal yard at Homestead Mill.

Despite who shot first, a battle began. The Pinkertons killed 2 and wounded 11 workers. The workers killed 2 and wounded 12 Pinkertons. Shots continued for ten minutes until both sides created shielded areas to hide behind. The workers hid behind scrap metal in the the scrap yard of the mill. The Pinkertons cut holes in the side of the barges. When the Pinkerton tug left with the wounded agents, it left the barges stranded at the mill.

At 9:00 a.m. the AA international president William Weihe rushed to the sheriff's office and asked him to arrange a meeting with Frick to avoid anymore violence. The sheriff did, but Frick refused the meeting, because he knew that if the violence continued the governor would call in the state militia. If the state militia had to come in, it would make the strikers look bad and would also permanently stop the striking. Eventually the sheriff attempted to contact the governor for help. The governor told him that he needed to handle the matter without the state militia.

Hugh O'Donnell

Hugh O'Donnell

At 4:00a.m., 5,000 men from nearby areas came to join the strike. Weihe asked Frick again to meet in order to stop the violence and at the same time urged the strikers to allow the Pinkertons to surrender. Hugh O'Donnell, was the leader of the strike. He said the only way the Pinkerton's would be allowed to surrender is if they were all charged with murder. At 5:00 p.m., the Pinkertons raised a white flag and two agents asked to speak with the strikers. O'Donnell guaranteed them safe passage out of town. The Pinkertons had to give their weapons to the strikers. As the Pinkertons crossed the grounds of the mill, the crowd threw sand and stones at them, spat on them and beat them.

Governor Robert Pattison of Pennsylvania

Governor Robert Pattison of Pennsylvania

The Pinkertons were marched through town to the Opera House which served as a jail for the Pinkerton agents. When two agents were beaten, the press turned against the strikers and began to support the Pinkerton agents. A special agent came and took the Pinkertons to Pittsburgh for trial. When they arrived, state officials said that they would not be charged. They were released without any charges. The steelworkers arranged to meet with the governor to discuss the situation. The governor did not want to intervene but because he had been elected by a political machine funded by Andrew Carnegie, he felt obligated to protect Carnegie's interests and not the steelworkers.

Major General George R. Snowden

Major General George R. Snowden

The governor sent Major General George R. Snowden and the state militia to talk with the union. The union welcomed the militia and declared that they were happy to work together to resolve the situation. Snowden made it clear to them that he sided with the owners. He informed them that they were breaking the law. He further explained that he had 4,000 soldiers surrounding the mill and another 2,000 outside the town. He told them that any attempts to stop new workers from coming into the plant would result in forceful takeover of the town. The state militia was able to get the new workers in and quickly began production again. A few union members attempted to stop production but militia fought them off with bayonets, wounded six union members.

On July 18, the town was placed under Martial Law. A few days later an assassination attempt was made on Frick's life. Though the attempt had nothing to do with the steel union, the union lost the support of the public. Hugh O'Donnell was removed as chair of the strike committee when he asked if workers could return to work if they accepted the cut in pay.

The Homestead Steel Mill Strike was a failure and resulted in needless deaths. It did teach future labor unions a valuable lesson though. It taught future unions that the public did not respond to violent tactics by labor unions. So, if unions wanted the support of the public, they needed to choose non-violent tactics.