Girls! They Rule the World!

Lawrence, Massachusetts

Lawrence, Massachusetts

In Lawrence, Massachusetts, the textile industry had become the center of the town's economy. By the early 20th century, most of the people who worked in the textile mills were immigrants. Most were unskilled laborers; about half the workforce were women or were children younger than 18. It was estimated that 36 out of 100 died people by the time they were 25 years old. Some of the workers lived in housing provided by the companies. The workers had to pay rent and the rent price did not go down when the factories reduced wages. Other workers lived in cramped tenement houses in the town. Tenement house rent was very expensive. The average worker at Lawrence earned less than $9 per week. Rent prices averaged about $3 - $4 a week.

New machines helped factories increase the speed of production. When production increased, factory managers would cut the workers' wages or lay off workers. Increased production and fewer workers made the work more difficult.

New machines helped factories increase the speed of production. When production increased, factory managers would cut the workers' wages or lay off workers. Increased production and fewer workers made the work more difficult.

Early in 1912, mill owners at the American Wool Company in Lawrence, Massachusetts, cut the worker's wages when a new law was passed that reduced the number of hours that women could work from 56 hours a week to 54 hours per week. They thought that because the workers came from so many different ethnic backgrounds that they would not be able to communicate in order to organize a successful strike.

When workers opened their pay envelopes and say their pay had been reduced, they walked off the job in protest. In the first week of the strike, angry workers walked from mill to mill hurling bricks and stones through mill windows. More and more workers joined the strike. During the first week 14,000 workers walked off the job in Lawrence and were followed by 9,000 more in the coming weeks.

The Industrial Workers of the World also called the I.W.W., was a radical labor union during this time. Their members were called Wobblies. The Wobblies offered to come in and help the striking textile workers. The workers told the I.W.W. that they wanted a 15% pay increase. They wanted managers to honor the 54 hour work week. They also wanted to be paid overtime pay at double the normal rate of pay. Finally, workers wanted to get rid of of bonus pay because it only rewarded a few people and encouraged everyone to compete to work longer hours.

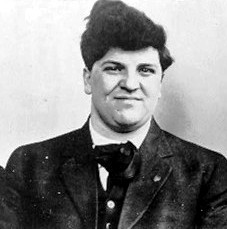

Joseph Ettor (No, I don't know what's up with his hair!)

Joseph Ettor (No, I don't know what's up with his hair!)

Joseph Ettor was an organizer for the I.W.W. He had experience with organizing strikes in the west and Pennsylvania. He knew several different languages. His ability to speak different languages helped him to communicate with the immigrant workers. He represented many different nationalities of immigrant workers including: Italians, Hungarians, French-Canadians, Slavs, and Syrians, and people from Portugal.

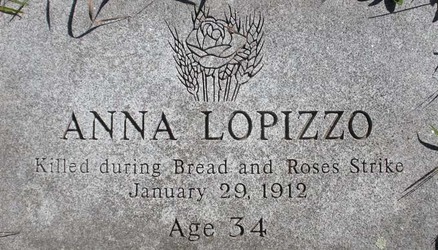

The city reacted with nightime militia patrols, turning fire hoses on strikers, and sending some of the strikers to jail. Groups elsewhere, often Socialists, organized strike relief, including soup kitchens, medical care, and funds paid to the striking families. On January 29, a woman striker, Anna LoPizzo, was killed as police broke up a picket line. Strikers accused the police of the shooting. Police arrested IWW organizer Joseph Ettor and Italian socialist, newpaper editor, and poet Arturo Giovannitti who were at a meeting three miles away at the time and charged them as accessories to murder in her death. After this arrest, martial law was enforced and all public meetings were declared illegal.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

The IWW sent some of its more well-known organizers to help out the strikers, including Bill Haywood, William Trautmann, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and Carlo Tresca, and these organizers urged the use of peaceful tactics. Newspapers announced that some dynamite had been found around town; one reporter revealed that some of these newspaper reports were printed before the dynamite had even been found. The companies and local authorities accused the union of planting the dynamite, and used this accusation to try to turn the public against the union and strikers. Later, in August, a contractor confessed that the textile companies had been behind the dynamite plantings, but he committed suicide before he could testify to a grand jury.

Children on their way to the train station

Children on their way to the train station

Striking was important to the workers. They wanted to take a stand and demand fair treatment. Infortunately, it was also costly. The I.W.W. helped strikers by arranging for their children to stay with foster families until the striking ended. About 200 children of strikers were sent to New York, where supporters had found foster homes for them. 5,000 people, mostly Socialists, turning out on February 10 to show the families and children their support. The strike had attracted a great deal of public attention and people felt sympathy for the strikers and their families. Lawrence authorities and state militia came to the train station where the children were supposed to board the train. Under government orders the militia clubbed and beat women, children, and supporters at the station. The authorities arrested many of the adults. The children were taken from their parents.

Helen Heron Taft

Helen Heron Taft

The U.S. Congress opened an investigation into the event. The House Committee on Rules heard testimony from strikers. President Taft's wife, Helen Heron Taft, attended the hearings to give her support. The investigation found that children were being abused and neglected. They discovered the brutal working conditions and found out about the poor pay. They learned that a third of mill workers, whose life expectancy was less than 40 years, died within a decade of taking their jobs. They learned about how workers developed respiratory infections such as pneumonia or tuberculosis from inhaling dust and lint and of the common accidents that took lives and limbs.

Strikers celebrate their victory

Strikers celebrate their victory

The mill owners, saw that the nation was against them. They feared that th government might issue more restrictions on them. So, on March 12, the mill owners gave into the strikers' demands. Workers gained a 15-percent increase in their pay, overtime compensation, and a promise not to retaliate against strikers. On March 14, the nine-week strike ended but it was not enough to satisfy the strikers.

Ettor and Giovannitti are acquitted

Ettor and Giovannitti are acquitted

Strikers led by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn held demonstrations because Ettor and Giovannitti were still in jail. On September 30, fifteen thousand Lawrence mill workers walked out in a one-day solidarity strike. The trial, finally begun in late September, took two months. The two men were acquitted on November 26.

The strike in 1912 at Lawrence is sometimes called the "Bread and Roses" strike because it was here that a picket sign carried by one of the striking women reportedly read "We Want Bread, But Roses Too!" It became a rallying cry of the strike, and then of other industrial organizing efforts, signifying that the largely unskilled immigrant population involved wanted not just economic benefits but recognition of their basic humanity, human rights, and dignity. The Bread and Roses Strike had an important impact on America. It showed that women could organize successful strikes across ethnicities and proved that women were a force to be reckoned with. It also would give women the feeling of empowerment they needed to gain the right to vote in 1920.

Click on the Bread and Roses Centennial Icon below to visit the Bread and Roses Interactive Website.