A Government For the People

anthracite coal

anthracite coal

Anthracite Coal is a natural, hard, shiny coal that burns slowly and gives intense heat. Anthracite coal has fewer impurities so it burns cleaner than soft coal, with almost no smoke, which made it very well-suited for heating. Anthracite coal was the most popular fuel for heating in the northern United States from the 1800s until the 1950s. The largest deposits of anthracite coal were in Northeastern Pennsylvania.

Anthracite Mining Town in Shenandoah, PA

Anthracite Mining Town in Shenandoah, PA

At the turn of the Twentieth Century, Big business industrialists controlled coal mining. They viewed their employees as a commodity. They believed the employees were simply another part of doing business. They made their employees live in mining towns close to the mines that they worked in. Industrialists controlled almost every aspect of miners' lives.

Miners strongly opposed the view that they were just a 'commodity'. The miners believed that they deserved the right to have a say in their working conditions, health and safety issues, their working hours and their rates of pay. Industrialists had cut the miners' wages for several years but their rents had stayed the same. The mine owners also charged high prices at the company stores that were deducted from the miner's wages.

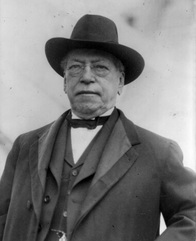

John Mitchell, President of the United Mine Workers of America

John Mitchell, President of the United Mine Workers of America

Miners had long complained about the lack of safety regulations and poor working conditions of mine work. John Mitchell was the President of a coal miners' labor union called the United Mine Workers of America. He organized a successful strike against the bituminous coal operators in the Midwest and western Pennsylvania. He gained these workers better working conditions and hoped to do the same for the anthracite coal miners of eastern Pennsylvania. The operators, headed by George F. Baer, President of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, would not give into any of Mitchell's requests. So, Mitchell called his men to strike.

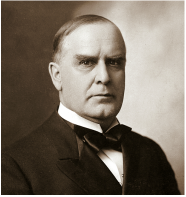

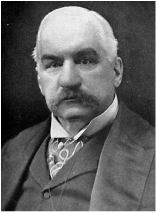

At this time William McKinley was running for president. He did not want to lose votes because miners were unhappy. McKinley's campaign manager knew that he could get J.P. Morgan to help end the strike. J.P. Morgan owned many of the railroads that were operated by men like George Baer. He did not want to lose money because of a strike and he wanted McKinley to win the election as well. So Morgan told Baer to compromise with Mitchell. So Baer was forced to give the miners a 10% wage increase.

President William McKinley

President William McKinley

It seemed like a happy ending. Mitchell had gained miners a wage increase. McKinley was elected president and Morgan did not lose money on a strike. Everyone was happy except the coal operators. They felt bullied into giving in to the coal miners. It made them angry, bitter, and stubborn. Any further compromises between miners and operators was going to be a struggle.

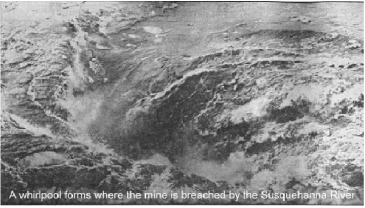

A mine cave in

A mine cave in

In 1902, Mitchell decided that the miners needed better working conditions. The mine owners were making huge profits but refused to improve working conditions, wages, or benefits for miners. Miners wanted higher wages because of the hazards and dangers involved with their jobs. Some of these hazards included roof falls, explosions, mine fires, underground flooding, "marsh gas" given off by coal which led to massive explosions, and coal dust that caused a chronic respiratory disease. Another issue miners had was child labor.

He asked the operators to improve the working conditions but the operators refused. In March, Mitchell met with anthracite laborers. He made a list of their demands for the operators. First, miners wanted operators to recognize the United Mine Workers Association as a union. They wanted the union to have a say so in all company decisions regarding workers. Secondly, they wanted a 20% increase in wages. Thirdly, they demanded a their shifts be reduced from a ten hour workday to an eight hour workday. Finally, they wanted a new wage system. They wanted to change the mining requirements. Operators paid miners by the number of coal cartloads that they mined. Miners wanted to be paid by the total weight that they mined. Mitchell, presented the miners demands to the operators but again, he was ignored.

On May 12, 1902, Mitchell called out 147,000 workers from the anthracite mines of Pennsylvania. The “Great Strike” had begun. Baer and the other operators had 5,000 hired guns to guard the mines. During this time, the law backed hired guns. Baer was sure Mitchell would back down and the strike would end. Mitchell did not back down. In fact, Mitchell told them that if the pumpmen, firemen and engineers, who kept the mines from flooding with water, did not receive an eight-hour workday within two weeks, they would withdraw from the mines on June 2. Without these men to pump the mines, the mines would flood and cost a great deal of money to repair. Mitchell was sure Baer would give into the miners demands. Baer did not give in, so the pumpmen, firemen and engineers left.

Brigadier General John P.S. Gobin

Brigadier General John P.S. Gobin

Tensions grew between miners and operators. Miners set fire to the fence surrounding the mine. After the fence was fixed, the hired guns saw a boy walking close to it. Afraid that the boy was going to set fire to the fence, the hired guns shot him. the boy was rushed to the hospital and the hired guns were arrested. Strikers intimidated workers who were not on strike. They called them on the telephone at midnight and threatened to blow up their homes with dynamite. Hired guns killed a man who tried to crawl over the fence and did not stop when ordered to. At this point, Brigadier General John P.S. Gobin was called in with 3000 National Guard troops to stop the violence.

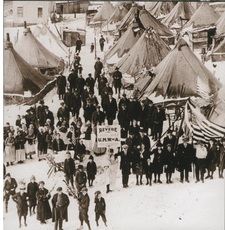

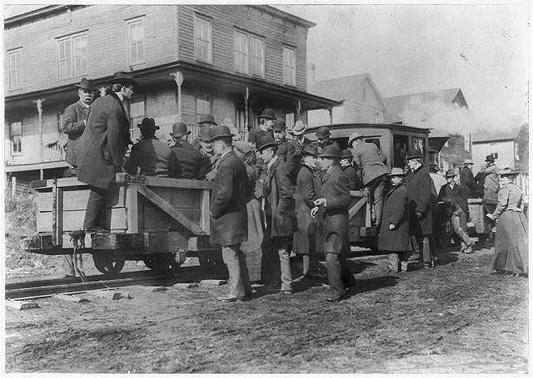

Strikers camp outside of the town as they strike.

Strikers camp outside of the town as they strike.

Gobin's arrival did not stop the strikers. Three hundred strikers stopped a train that was carrying workers and hired guns to the mine. When the train tried to continue on its way, the strikers hurled rocks and fired their guns on it. The men inside dove to the ground as shards of glass fell on them. Gobin gave the order to fire at will if attacked and the entire force of the National Guard, 10,000 strong, was called into Pennsylvania.

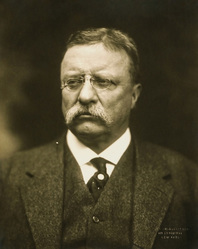

President Theodore Roosevelt

President Theodore Roosevelt

President Theodore Roosevelt sympathized with the miners but he knew the violence had to end. Though he had to legal grounds to intervene, he considered himself to be “the steward of the people." Roosevelt intervened in the strike by personally enforcing what he thought was best to resolve the matter, whether the law allowed him to or not. The feud between strikers and operators was not only hurting the American economy but winter was coming. People would freeze if the coal miners continued to strike.

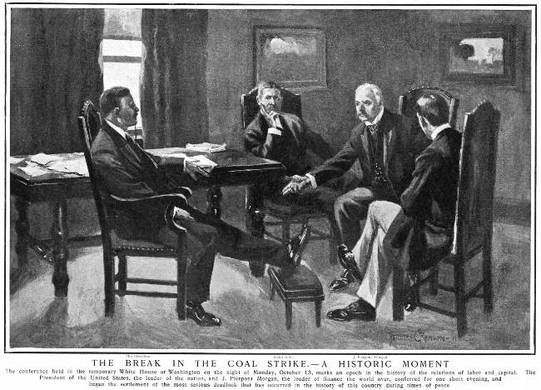

Roosevelt sent telegrams to the laborers and the operators to hold a meeting with him on October 3 in Washington. At the meeting, Baer spoke for the gathered coal operators and Mitchell for the laborers. President Roosevelt, the Commissioner of Labor, the Attorney General, and Roosevelt’s secretary, gathered to hear the arguments.

Roosevelt explained that he did not want to become involved but that it was very important that the two sides came to an agreement because the strike was not just affecting the laborers and operators. It was hurting the American people. Mitchell responded by saying that he welcomed the President's intervention. He told Roosevelt that he would be happy to share the miners grievances with him and get his input on the matter. Baer was angry. He reminded the president that it was not in his right to intervene. He let the president know that he was angry that his right to run the business as he saw fit had been violated. He further said that he was angered by a government that would support the strikers who were breaking the law. The meeting went nowhere. Both sides left with nothing worked out.

J.P. Morgan

J.P. Morgan

Roosevelt was not going to let this fly. Roosevelt went to J.P. Morgan and they made a contract that allowed the president to assign an arbitration committee to settle the strike. Morgan made Baer and the other operators sign the contract. They signed it, but in return they demanded that the president set up the committee composed of five men—a military engineer, a mining engineer, a judge, an expert in the coal business, and a well known sociologist.” The list just so happened to lack anyone to be in favor of the laborers.

The Anthracite Coal Commission investigates conditions at the mines

The Anthracite Coal Commission investigates conditions at the mines

Mitchell found out about the arrangement. He demanded that the president add a labor man and a Catholic to the committee so that the workers had people that would look out for their interests. Roosevelt agreed. He brought together a group of men that met the requirements of both sides and they became the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission. The group would listen to both sides of the argument and would determine a solution that both sides would have to legally abide by.

Mitchell called off the strike on October 23. It had lasted for 163 days. There were seven recorded deaths and numerous stories of terror and crime committed on both sides, but the “Great Strike” earned a reputation as being one of the most organized strikes to date. The Commission travelled to the anthracite mines for 10 days to personally inspect the conditions under which the miners worked. Then on November 14, the Commission began its hearings at the Lackawanna County Courthouse.

Mitchell called off the strike on October 23. It had lasted for 163 days. There were seven recorded deaths and numerous stories of terror and crime committed on both sides, but the “Great Strike” earned a reputation as being one of the most organized strikes to date. The Commission travelled to the anthracite mines for 10 days to personally inspect the conditions under which the miners worked. Then on November 14, the Commission began its hearings at the Lackawanna County Courthouse.

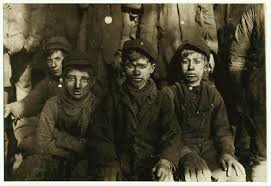

Breaker Boys

Breaker Boys

The hearings lasted until March of the next year. During the process, 558 witnesses were heard, ranging from unionists to nonunion workers attacked during the strike, to wives of workers and breaker-boys younger than nine years of age. Finally, on March 22, 1903, the Commission announced its verdict: the miners won a 10% increase in wages and a nine-hour workday. Coal was still paid by the cart load, and the UMWA was still unrecognized as a union. This ended the Great Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902.

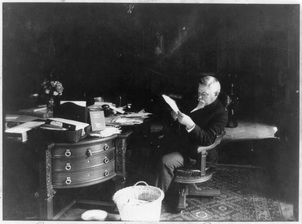

Samuel Gompers, President of the American Federation of Labor

Samuel Gompers, President of the American Federation of Labor

The result of the strike were very controversial. Everyone had their own opinions about who was wrong and who was right. Despite the controversy, the strike did help to increase union membership in all sorts of unions. Samuel Gompers, who founded the American Federation of Labor, said that he viewed the strike as “the most important single incident in the labor movement in the United States.” This was because it was for the most part a successful strike that gained the sympathy of the American public.

Gov. Samuel Pennypacker created the Pennsylvania State Police after the Great Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902.

Gov. Samuel Pennypacker created the Pennsylvania State Police after the Great Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902.

The Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902 had a great impact on the United States. First of all, the strike led states to form state police forces and do away with hired gun commissions. No longer could companies and businessmen hire police to enforce what they wanted. Now state police would work for both sides to uphold the law. Secondly, the strike promoted a new idea in politics and society. Theodore Roosevelt introduced the idea of Progressivism, or the greatest good for the greatest amount of people. Beginning at the turn of the 20th century, Progressives fought to limit the power and influence of the wealthy. They fought for better living conditions for the majority of Americans, especially laborers in factories and mines. Roosevelt made the government Progressive. He made the government a protector of the people in feuds between capital and labor.

W.E.B. DuBois

W.E.B. DuBois

After Roosevelt established a progressive government, new laws were written to protect the people. W.E.B. DuBois created the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, commonly called the NAACP, to help African Americans gain equal treatment, better educations, and better jobs. In 1905 the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed that forbade selling bad foods and required a list of ingredients on all foods and drugs. Finally it helped women gain universal suffrage, or the right to vote in 1920 through the 19th Amendment. Thanks to the anthracite strike of 1902, Roosevelt was able to employ the means of the federal government in improving the standard of living for all Americans.