James Bridger

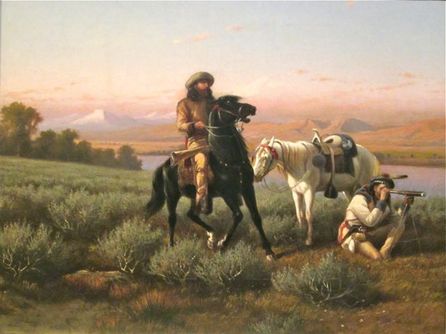

“Jim Bridger with Sir William Drummond Stewart”

Painted by Wm. de la Montagne Carey in 1872

“Jim Bridger with Sir William Drummond Stewart”

Painted by Wm. de la Montagne Carey in 1872

James Bridger (Old Gabe) was in good company when he signed on with Hugh Glass, Jedediah Smith, and Thomas Fitzpatrick to be a member of General Ashley's Upper Missouri expedition. At the age of 17, he was the youngest member of the expedition. This was beginning of a long and colorful career in the mountains for Jim Bridger.

Bridger rose to the status of the quintessential mountain man. Biographer Grenville Dodge described him as:

"a very companionable man. In person he was over six feet tall, spare, straight as an arrow, agile, rawboned and of powerful frame, eyes gray, hair brown and abundant even in old age, expression mild and manners agreeable. He was hospitable and generous, and was always trusted and respected."Bridger had a remarkable sense of humor and he especially loved to shock tenderfeet and easterners with his tall tales. He would tell of glass mountains, "peetrified" birds singing "peetrified" songs, and reminisce about the days when Pikes Peak was just a hole in the ground. These stories were related in such a serious manner as to fool even skeptics into believing them, making Jim's laughter all the louder when his ruse was revealed.

All of these attributes served Bridger well, and made him adaptable to just about every situation he found himself in. By the end of his lifetime, Bridger could claim the titles of trapper, trader, guide, merchant, Indian interpreter and army officer.

Bridger rose to the status of the quintessential mountain man. Biographer Grenville Dodge described him as:

"a very companionable man. In person he was over six feet tall, spare, straight as an arrow, agile, rawboned and of powerful frame, eyes gray, hair brown and abundant even in old age, expression mild and manners agreeable. He was hospitable and generous, and was always trusted and respected."Bridger had a remarkable sense of humor and he especially loved to shock tenderfeet and easterners with his tall tales. He would tell of glass mountains, "peetrified" birds singing "peetrified" songs, and reminisce about the days when Pikes Peak was just a hole in the ground. These stories were related in such a serious manner as to fool even skeptics into believing them, making Jim's laughter all the louder when his ruse was revealed.

All of these attributes served Bridger well, and made him adaptable to just about every situation he found himself in. By the end of his lifetime, Bridger could claim the titles of trapper, trader, guide, merchant, Indian interpreter and army officer.

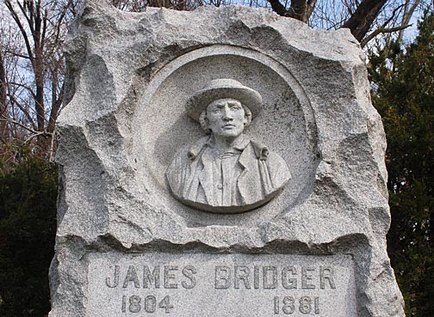

Jim Bridger's gravestone in Independence, Missouri

Jim Bridger's gravestone in Independence, Missouri

After working for Ashley, Bridger trapped the Rocky Mountains with various companies and partnerships. Renowned by his peers, Bridger was an able brigade leader and an excellent trapper. Year after year he was able to avoid Indian attack and turn a profit from his trapping.

One particular discovery early on in Bridger's career brought him lasting celebrity. To settle a bet in the winter camp of his trapping party of 1824, Bridger set out to find the exact course of the Bear River from the Cache Valley. He returned and reported that it emptied into a vast lake of salt water. The men were convinced he had found an arm of the Pacific Ocean. In reality, he was the first white man to view The Great Salt Lake.

Bridger's most important discovery would come years later, in 1850. Captain Howard Stanbury stopped at Fort Bridger and inquired about the possibility of a shorter route across the Rockies than the South Pass. Bridger guided him through a pass that ran south from the Great Basin. This pass would soon be rightfully called Bridger's Pass and would be the route for overland mail, The Union Pacific Railroad line and finally Interstate 80.

Although he would remain a trapper, Bridger easily turned to other means of income after the softening of the beaver market in the 1840's. In the summer of 1841, Bridger and Henry Fraeb began building a crude structure on the west bank of the Green River. They intended it as a trapping and trading base. Later that summer, the first wagon load of overland missionaries and emigrants rolled up and Fort Bridger was born. Jim did not recognize the significance of that moment, but in the coming years he realized the potential of his crude building. Years later he described it:

"I have established a small store, with a Black Smith Shop, and a supply of Iron on the road of the Emigrants on Black's fork Green River, which promises fairly, they in coming out are generally well supplied with money, but by the time they get there are in want of all kinds of supplies. Horses, Provisions, Smith work &c brings ready Cash from them and should I receive the goods hereby ordered will do a considerable business in that way with them. The same establishment trades with the Indians in the neighborhood, who have mostly a good number of Beaver amongst them."

James Bridger died on a Missouri farm in 1881. At 77, he was one of the last living mountain men.

One particular discovery early on in Bridger's career brought him lasting celebrity. To settle a bet in the winter camp of his trapping party of 1824, Bridger set out to find the exact course of the Bear River from the Cache Valley. He returned and reported that it emptied into a vast lake of salt water. The men were convinced he had found an arm of the Pacific Ocean. In reality, he was the first white man to view The Great Salt Lake.

Bridger's most important discovery would come years later, in 1850. Captain Howard Stanbury stopped at Fort Bridger and inquired about the possibility of a shorter route across the Rockies than the South Pass. Bridger guided him through a pass that ran south from the Great Basin. This pass would soon be rightfully called Bridger's Pass and would be the route for overland mail, The Union Pacific Railroad line and finally Interstate 80.

Although he would remain a trapper, Bridger easily turned to other means of income after the softening of the beaver market in the 1840's. In the summer of 1841, Bridger and Henry Fraeb began building a crude structure on the west bank of the Green River. They intended it as a trapping and trading base. Later that summer, the first wagon load of overland missionaries and emigrants rolled up and Fort Bridger was born. Jim did not recognize the significance of that moment, but in the coming years he realized the potential of his crude building. Years later he described it:

"I have established a small store, with a Black Smith Shop, and a supply of Iron on the road of the Emigrants on Black's fork Green River, which promises fairly, they in coming out are generally well supplied with money, but by the time they get there are in want of all kinds of supplies. Horses, Provisions, Smith work &c brings ready Cash from them and should I receive the goods hereby ordered will do a considerable business in that way with them. The same establishment trades with the Indians in the neighborhood, who have mostly a good number of Beaver amongst them."

James Bridger died on a Missouri farm in 1881. At 77, he was one of the last living mountain men.